New research affirms a unique peptide found in an Australian plant can destroy the No. 1 killer of citrus trees worldwide and help prevent infection.

Huanglongbing, HLB, or citrus greening has multiple names, but one ultimate result: bitter and worthless citrus fruits. It has wiped out citrus orchards across the globe, causing billions in annual production losses.

All commercially important citrus varieties are susceptible to it, and there is no effective tool to treat HLB-positive trees, or to prevent new infections.

However, new UC Riverside research shows that a naturally occurring peptide found in HLB-tolerant citrus relatives, such as Australian finger lime, can not only kill the bacteria that causes the disease, it can also activate the plant’s own immune system to inhibit new HLB infection. Few treatments can do both.

Research demonstrating the effectiveness of the peptide in greenhouse experiments has just been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

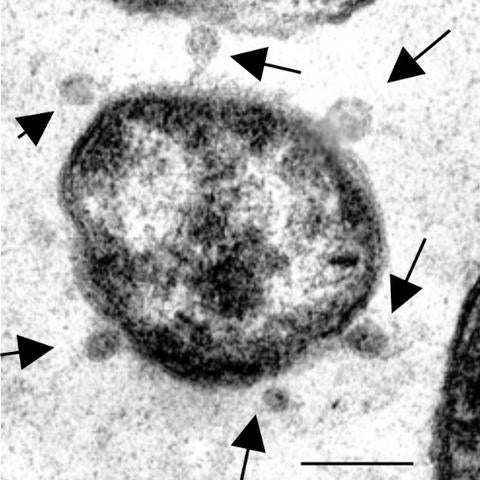

The disease is caused by a bacterium called CLas that is transmitted to trees by a flying insect. One of the most effective ways to treat it may be through the use of this antimicrobial peptide found in Australian finger lime, a fruit that is a close relative of citrus plants.

“The peptide’s corkscrew-like helix structure can quickly puncture the bacterium, causing it to leak fluid and die within half an hour, much faster than antibiotics,” explained Hailing Jin, the UCR geneticist who led the research.

When the research team injected the peptide into plants already sick with HLB, the plants survived and grew healthy new shoots. Infected plants that went untreated became sicker and some eventually died.

“The treated trees had very low bacteria counts, and one had no detectable bacteria anymore,” Jin said. “This shows the peptide can rescue infected plants, which is important as so many trees are already positive.”

The team also tested applying the peptide by spraying it. For this experiment, researchers took healthy sweet orange trees and infected them with HLB-positive citrus psyllids — the insect that transmits CLas.

After spraying at regular intervals, only three of 10 treated trees tested positive for the disease, and none of them died. By comparison, nine of 10 untreated trees became positive, and four of them died.

In addition to its efficacy against the bacterium, the stable anti-microbial peptide, or SAMP, offers a number of benefits over current control methods. For one, as the name implies, it remains stable and active even when used in 130-degree heat, unlike most antibiotic sprays that are heat sensitive — an important attribute for citrus orchards in hot climates like Florida and parts of California.

In addition, the peptide is much safer for the environment than other synthetic treatments. “Because it’s in the finger lime fruit, people have eaten this peptide for hundreds of years,” Jin said.

Researchers also identified that one half of the peptide’s helix structure is responsible for most of its antimicrobial activity. Since it is only necessary to synthesize half the peptide, this is likely to reduce the cost of large-scale manufacturing.

The SAMP technology has already been licensed by Invaio Sciences, whose proprietary injection technology will further enhance the treatment.

Following the successful greenhouse experiments, the researchers have started field tests of the peptides in Florida. They are also studying whether the peptide can inhibit diseases caused by the same family of bacteria that affect other crops, such as potato and tomato.

“The potential for this discovery to solve such devastating problems with our food supply is extremely exciting,” Jin said.

This UCR News article was written by Jules Bernstein and can be viewed here, while the PNAS paper can be viewed here.